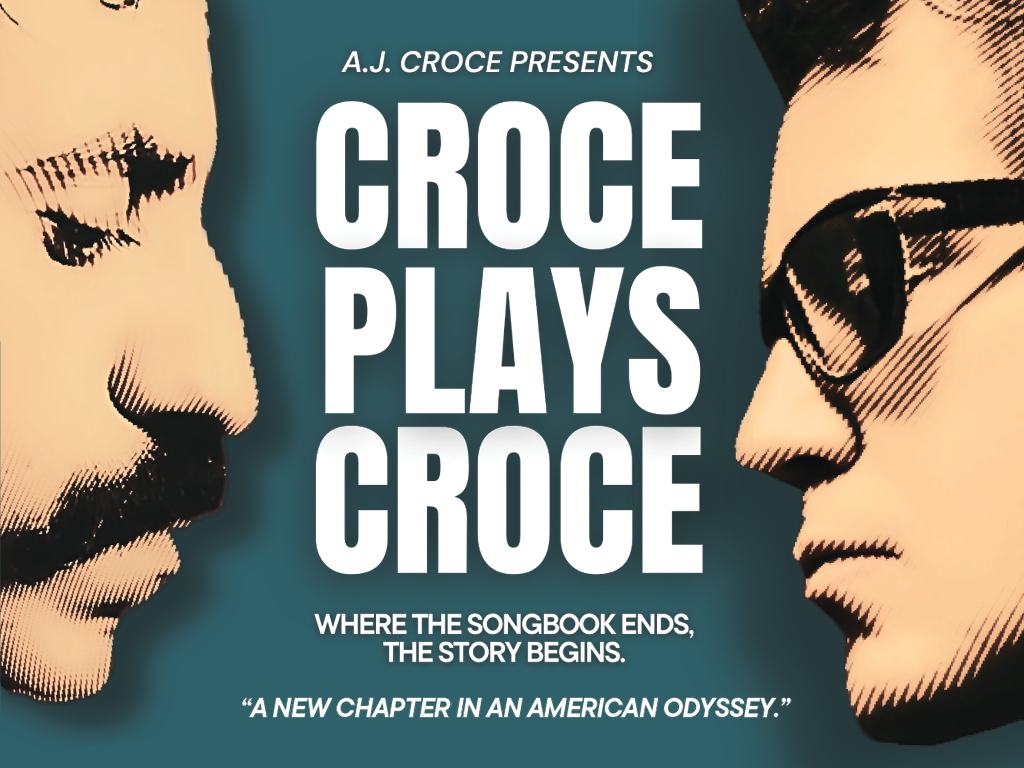

Between interpreting a legacy and writing his own, A.J. Croce threads the needle where the songbook ends and the story begins. Following a stretch of shows that has held more weight than most artists ever shoulder, I asked the singer-songwriter how it felt to shift from Croce Plays Croce, a historically significant tour honoring his father Jim Croce’s body of work, back into his own. Was it freeing or challenging? “Both,” he answered without hesitation, then unpacked the duality of standing in the light of a legacy while casting a new silhouette.

“I think I made so many people aware of my music through his that people weren’t really sure what they were going to get when they saw me play. There were fans who saw me in my early records with a lot of press and TV appearances, but they weren’t necessarily aware of what I’d been doing lately. It’s been a challenge teaching them about who I am, in a good way. And of course, I’m still playing his music because that’s part of the show, and a lot of folks really want that. Both facets are exciting because playing my own music as the focus has been a lot of fun.”

Since we spoke, he’s announced a new run of dates and a new chapter of Croce Plays Croce — proving that the demand, and his willingness to meet it, are both going strong. The idea that he might still be introducing himself to audiences over thirty years into a career with eleven albums says a lot about how legacy can both light the way yet come with a long shadow. A.J. carries both truths with ease, balancing the uncanny vocal resemblance with a singular talent.

When I asked what part of his dad’s spirit still shows up unexpectedly while he’s creating, he didn’t mention pressure, or anything like that. He talked about his dad’s record collection. “I grew up with that record collection. It was so deep, and it was so amazing. I joke that Ray Charles was my gateway drug, and he certainly was, especially in the sense of losing my sight as a kid. But from a really early age, I was allowed to use the record player and listen to all of the records.”

Curiosity laid a foundation that was expansive and self-directed. And like Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder was part of that pantheon of musical guides. He adds, “Honestly, all of the blind musicians: Blind Blake, Blind Willie McTell, Blind Lemon Jefferson… There were great old string bands and early country stuff. Bob Wills and Lefty and Hank Williams. There was a ton of really great early rock and roll and R&B, so Sam Cooke, Solomon Burke, and Otis Redding. All of the cool ‘50s and early ‘60s soul music that informed my music to such a great degree.”

Some legacies feel impossibly compressed, yet impossibly complete. Otis Redding and Hank Williams were so young when they passed, yet they left behind a staggering string of songs. The same is true for Jim Croce. He wrote all those classic songs in just the last 18 months of his life. “It’s an amazing thing. The first two albums were written in about a six-month period. Honestly, for him, ‘Time in a Bottle’ was an epiphany. I have a hundred home recordings of his, which I grew up with.”

“Time in a Bottle” wasn’t just a hit for Jim Croce. It was a threshold crossed. He wasn’t even sure what he was going to do with his life, or if music would work out financially – or at all. That one song did more than shape Jim Croce’s trajectory; it cracked something open. Once that floodgate gave, what came after was more than songwriting; it was storytelling lived fully. “It just happened to be something that was the first of many songs where he really discovered not just the ballad, but how the character songs were going to develop and how he put himself in them. All of his life experience went into those songs like ‘Leroy Brown,’ ‘Don’t Mess Around with Jim,’ and ‘Car Wash Blues.’”

Then, in 1973, Jim’s life was tragically cut short in a plane crash. A.J. was not yet two years old, but forever marked by that loss. The same commitment to craft and storytelling that defined his father’s work pulses through A.J.’s music today. His latest release, Heart of the Eternal, has already landed on multiple Billboard charts. But that’s hardly the metric that matters most. “It’s rewarding in one way. It gives you a sense that someone out there likes you, but I’ve never really thought that was going to make a big difference in my life. I’ve been fortunate in that regard. I’ve had 20-something songs on the charts, and all different charts. I’m a person who is really dedicated to all different crafts that I have taken on, whether it’s as a piano player, a guitar player, a songwriter, a singer… I’ve dedicated myself to the art.”

Like A.J., Shooter Jennings knows what it means to carry a father’s story while carving a sound of his own— and he approaches that process with a musician’s mindset, using the studio as an instrument. “He has something in common with all the great producers I’ve worked with: an open mind, always looking for that happy accident. He knows as well as any great producer that when something happens differently than planned—that could be the thing that makes all the difference. A lot of producers, especially those who start as engineers before becoming producers, tend to be more rigid. Shooter is a musician first, but his strongest abilities lie at the recording console. I think he really understands how the room and all the equipment work together.”

Stepping into Sunset Sound wasn’t just a return to an iconic space, but to a memory quietly waiting in the walls. “It’s a wonderful place to record. It had been a long time since I was at Sunset Sound. I had a flashback while I was in there when Studio Three was just first finished. I think my mom was going back to playing music after almost 10 years of not recording or performing. I remember falling asleep underneath that same console they have there now. I think I played on something in one of the other studios. It was that Studio Three. ‘Oh my God, I know I’ve been here.’ I remembered exactly where it was and where I was, and it was kind of a surreal experience.”

That memory unlocked another for me – one he sometimes shares onstage, about being a kid at an adult party where the most sober person around was tasked with putting him to bed. Their idea of a lullaby was an inappropriate Irish tune. “I’ll always thank Rod Stewart for that,’ he deadpans to the crowd.

“It’s kind of a long-winded story, but it does have a punchline,” he tells me. “My mother was working with the producer who had worked with him and Elton John. They lived next to each other in the ’70s in Los Angeles on Doheny Drive. I remember going up there as a kid, just being around that.” This was before he regained vision in his left eye, so he doesn’t recall the visuals, just the smells and sounds. “I was called up 15 years later to go on tour with Rod Stewart along the West Coast. It was really fun, inspiring—and terrifying. Sadly, I never got to tell Rod Stewart about it because the venues were so big, outdoor amphitheaters. I had to leave before he arrived or wait five hours after the show. But it was a sweet experience.”

Heart of the Eternal features guests with deep roots: bassist David Barard (Grammy winner who played with Dr. John for nearly four decades), drummer Gary Mallaber (Van Morrison’s Moondance and Tupelo Honey), and guitarist James Pennebaker (Delbert McClinton, Jimmie Dale Gilmore). “I put the band together piece by piece. After recording with Allen Toussaint in New Orleans, I asked him for recommendations. I played a couple small shows—one at the Maple Leaf, one at the Mint—and invited people to sit in to get a sense of things. Then I held an audition there. The first person at the uptown show was David Barard. I hadn’t seen him in 15 years but knew him from his long run with Dr. John. David met Mac [Rebennack] through Allen and toured with him around Southern Nights. He also worked with Patti LaBelle and Etta James—who was a label mate of mine and someone I’d sat in with—and the Nevilles, who I’ve played with a lot. My first tour was with B.B. King, so David and I had many connections.

“Around 20 years ago, Gary Mallaber came into a demo session I was doing in L.A., and it just clicked. I love the records he did with Van Morrison—Moondance, His Band and the Street Choir, St. Dominic’s Preview. You hear him hit that snare, and it’s like hearing ‘Caravan.’ It all makes sense. He spent 28 years with Steve Miller and played with Joe Walsh and Peter Frampton, bringing a rock and roll edge I needed. While David and Gary are stylistically different, I figured their common ground would be something special. I’m proud we captured some of that. Ironically, it was the psychedelic soul of ‘I Got a Feeling’ and the garage rock feel of ‘Hey Margarita’ that gelled best.”

A.J.’s been writing on guitar for 25 years, but playing all these Croce shows made him more confident stepping out on both lead and rhythm guitar for the new album. On “I Got a Feeling,” he plays lead, having written the hook on tour and guided the arrangement so the keyboard complements it perfectly. “That Vintage Vibe I’m playing runs through a fuzz pedal and a tiny amp to create that real funky tone.”

“Hey Margarita” cuts through with a gritty guitar tone that nods to Link Wray, powered solely by vintage amps pushed just right. “It’s just a small setup like my stage rig: a late-’60s Deluxe Reverb and a ’50s Tweed Champ.”

When A.J. talks about his earliest influences, it’s less a list and more a constellation — each star connected by sound, soul, and history. “It became part of my musical language. It’s part of my vocabulary,” he says, reflecting on the solace he found in Ray Charles and Stevie Wonder. “And it’s informed a lot of other things.” Tracing that lineage leads through a century of pianistic storytelling. “By listening to Ray Charles, there were a lot of things that came to me in different ways. Fats Waller was an artist I was really inspired by. He was the whole package: comedian, songwriter, singer, and pianist.” From there, he discovered other pioneers who broke sound barriers by breaking rules, such as Little Richard and Fats Domino. He adds, “From some of the music like Fats Waller, I started moving forward and discovered Thelonious Monk through Fats Waller.”

But Waller’s intricate left-hand work wasn’t immediately accessible. “I couldn’t play that stuff initially,” he says. I point out to A.J. how he now uses the lower register not just for accompaniment but as a percussive engine, like Dr. John treating the piano as his own rhythm section. “I came to things in different ways,” he replies. “From Ray Charles, I went back to Charles Brown, Louis Jordan, all that jump stuff. And in that period, Big Joe Turner and Pete Johnson were hugely influential.”

By the time he was a teenager, he was already a human jukebox with a foot in multiple scenes. “I would play old standards, blues, R&B—Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, even Toussaint—when I was younger, playing jazz clubs, blues clubs, rock and roll clubs. I played alone. Some places didn’t even have amplification, so I was shouting over my piano, which eventually caused vocal issues for a couple years.” But there was a payoff. “That music really inspired me. I developed a playing style that let me be the whole band—to accompany myself and perform solo as well as with a group.”

It’s this versatility that makes his rapport with bassist David Barard so seamless; he’s obviously a piano player’s bass player, having played with Dr. John for almost 40 years. “He knew – Dr. John never played anything the same way twice. Allen Toussaint never played the same thing twice. He played with Jon Cleary as well, who never plays the same way twice. He may not know where I’m going, but he knows where I’m inclined to go,” he laughs.

The album builds on experiments with Shooter Jennings on the old Sunset Sound Steinway, but A.J.’s approach was colored in part by his past work with producer Mitchell Froom and Froom’s vintage-forward sensibility. “Mitchell, you might know from his work with Tom Waits, Elvis Costello, Crowded House… He’s got a studio full of amazing old instruments, amplifiers — all kinds of things. His approach is completely the opposite of the way I was taught. I was taught to mic a piano by Al Schmitt, the iconic engineer. On my first recordings in New Orleans, he was the engineer. He said, ‘This is how I mic’ed this Ray Charles album, or this Art Tatum album.’”

But Mitchell flipped the script. “These old instruments have this beautiful tone. It’s innate, it’s part of the instrument. Let’s see how we can make it sound different than it’s ever sounded before.” It wasn’t just a technical shift; it was a philosophical one. “That really changed my perspective about vintage instruments and recording. My approach has always been: let’s get the best mics we can, go through the best channels, and make it sound great — which still works. But his approach opened up a world of possibilities.

“I took that to Shooter, and he went wild with it. We were using a slapback pedal on the piano. We were using fuzz. We were using actual guitar pedals on it, to create in a way that’s completely different than if you just added those effects in the control room. You had mics going through the guitar pedal. But then you also had beautiful ‘50s, ‘60s Neumanns capturing the quintessential tone of that Steinway. You have multiple mics, and one of them is going through a guitar pedal or some kind of effect to create an ambiance. That was so much fun to do because we just kind of went crazy with it.”

Writing daily is just part of A.J.’s rhythm. “When I feel good about a song, I play it live. I teach the band, we run through it at soundcheck, or I’ll just play it alone and say, ‘Hey, I’ve got a new song; I want to play it for you.’ He keeps it to one new song a night. “I don’t feel comfortable doing more. They came to hear whatever they came to hear—it wasn’t necessarily the song I wrote that day or last week—but it gives me a really good sense of how the audience would like it. Every song on the new album passed that test—except one. ‘Finest Line,’ I tried out live.”

“Finest Line” has the dreamy feel of a Laurel Canyon cut, wrapped in piano lines and wistful exchange. Croce originally wrote it on guitar but revisited it on a whim the day he flew to Los Angeles. “I started playing it on piano, and I played it over the phone to my girlfriend. She said, ‘oh my God, what song is that? And I said, ‘I think I’ve played this for you, but I played it for you on guitar.’ I might’ve been a little precious with it, but it just felt like it needed it because I knew the words were so simple, it had to resonate.” Still unsure, he presented it to Shooter. “It was the last song I showed to Shooter and said, ‘I’m not sure if this is right or not.’ He said, ‘I love it. I think we should do it.’” Midway through tracking, Margo Price dropped in. “She loved what she was hearing,” Croce recalled. She said, ‘I’d love to sing with you if there’s a song you have. I would be happy to do a duet.’

“I pulled the lyrics to it out and realized if I cut the verses in half that it was really emotional. It becomes so conversational. I can hear the influence of Leonard Cohen in it. There’s a period in the late ‘60s where there were a lot of groups that were using baroque influences. Procol Harum did that a lot. So, it was kind of coming from that place musically. And you can also hear more modern artists, like an Elliott Smith could have done that song.” As for Margo’s involvement, it came naturally, even unexpectedly. “I have a friend who sings with her from time to time and a guy who lives in my neighborhood who’s played guitar with her on and off for many years, so we had mutual friends, but I wasn’t expecting to see her even collaborate.”

On the song “Reunion,” a co-write with John Oates, the idea was sparked by a story Oates shared with A.J., about his 100-year-old father looking forward to reuniting with his late wife. It struck a chord, given A.J.’s own experience losing his wife in 2018. He and Oates brought their own distinct version to it. When asked if it was a reflection of the different emotional places they were coming from, he says, “I think it was a combination. John is a wonderful person to collaborate with. He said, ‘I feel like it should be a gospel kind of song.’ But he was playing it in 4/4, and I said, ‘Well, we gotta play it in either 3/4 or 6/8 – otherwise it’s not gonna feel like a gospel song.’ That’s how I started playing the part that I was playing.

“(Oates) actually saw my folks play at the Philadelphia Folk Festival in like ’65 or ’66. He’s a huge fan of all kinds of American roots music. Big Mississippi John Hurt fan. As I am. John Hurt really was one of the musicians who taught me stride, because what he’s doing with both his hands, playing the kind of ragtime guitar or country blues; his fingerpicking style is very much like the left hand of Fats Waller. I learned how to play those stride lines by playing John Hurt with my left hand, and then playing the melody and changes with my right.” His father had a connection to Hurt, too: “He even interviewed him when he was a DJ, back in the early ’60s during the big folk scare.”

While A.J. often brings the music and co-writes lyrics from there — “that’s how it generally works, in 98% of the cases” — he found in Oates a rare creative partner. “He has such an understanding of music theory and the possibilities of where something can go. It was wonderful to collaborate with someone who has such a wealth of experience and knowledge when it comes to songwriting.”

Genre matters far less than soul. “How do I borrow from this, pay respect to it, and still make it sound like something you’ve never heard before? That’s the challenge. How do I make it my own without it sounding derivative or trite?” That idea lives in the album’s title, Heart of the Eternal. If you pick up one of the songs on the album, you run into a problem: that’s the song people go to on the record, and maybe that’s your goal, but they may not look for anything beyond that song if it doesn’t resonate for them.”

He traces the lineage back through earlier projects like Cantos and Cage of Muses, the latter named after how ancient scholars described the Library of Alexandria—as a repository of inspiration, a cage of muses. Heart of the Eternal is in line with that philosophy, he says: “It refers to the music, and to the art of sharing it.”