After years of holding down the heartbeat of New Orleans from the wings—as touring pros, first-call sidemen, and trusted studio hands—the members of Captain Buckles step into their own spotlight with Hurry Up. Before forming Captain Buckles, the members had performed with each other in various line-ups for years, touring as backing musicians with national and international acts like Eric Lindell, Samantha Fish, Russell Batiste, John “Papa” Gros, Glen David Andrews, and many others.

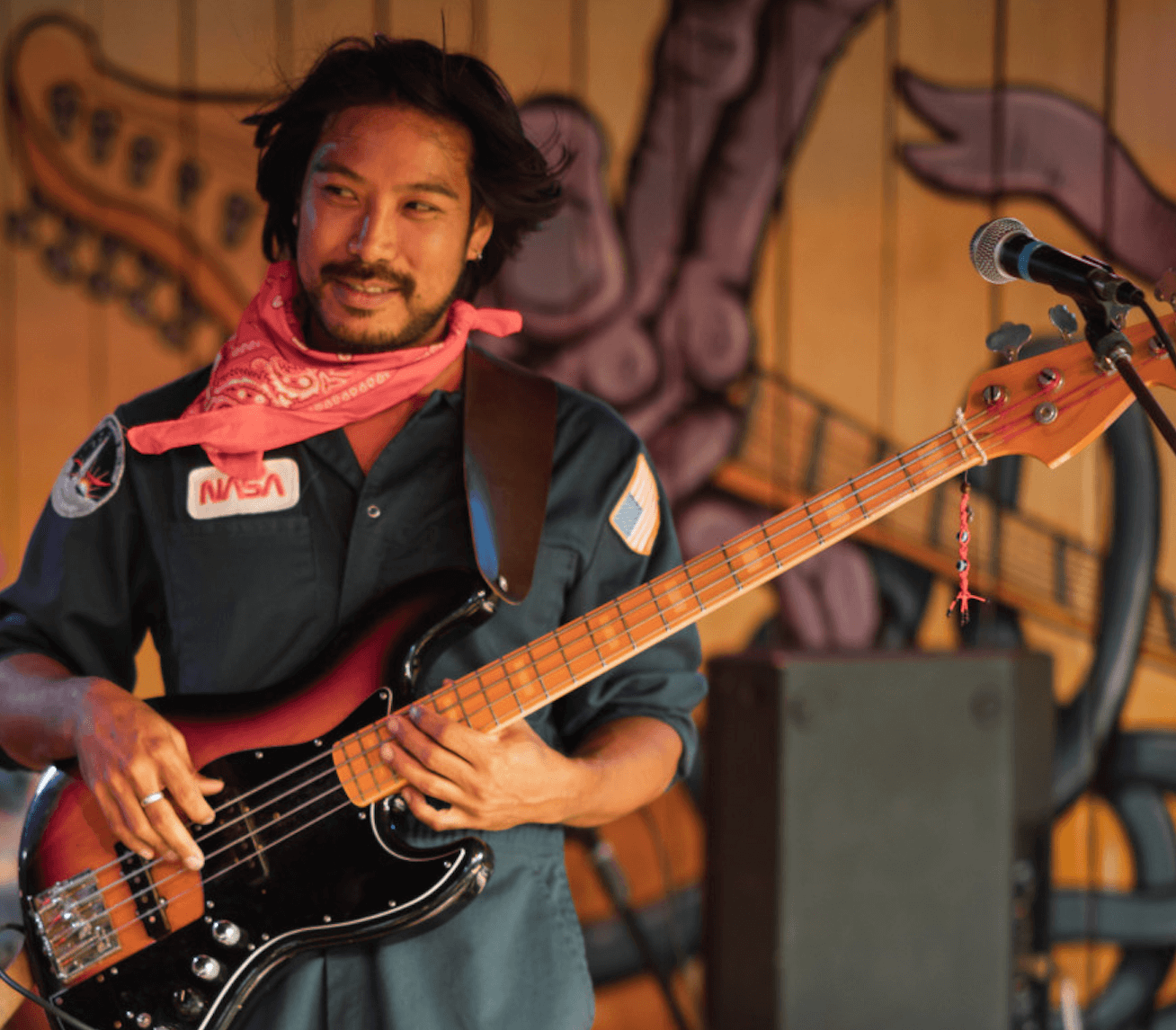

Recorded at Dockside Studio and supported by a Threadhead Cultural Foundation grant, Hurry Up moves with the roaming rhythm of New Orleans, informed by the band’s spirit of experimentation and the community that believed in them. American Blues Scene is proud to present the exclusive streaming premiere of the album, as well as to speak with bassist and bandleader Smitti Supab about the chemistry, collective trust, and creative freedom that brought the band together.

All of you have deep roots in the scene as touring and session musicians. How did that history shape the decision to come together and make this record as your own band?

It’s been quite an experiment and an adventure to get to this point because of this history, for sure. A lot of us have worked together in separate projects, sometimes for years, and I think these years of individually pursuing our own goals plays an integral part in bringing us together now. We’re much clearer now about what our personal desires and views and musical goals are, and I think that it’s nothing short of a miracle that they kind of align enough such that we have an album that we’re stoked about releasing!

Hurry Up doesn’t sound like a debut that’s asking permission. What did you want this record to say about who you are as a band?

Before we went into the studio and during the sessions, I’m not sure what I wanted the record to say about the band. I do know that I wanted it to sound natural, the way we sound live when we play together, and not too complicated and overly thought-out. I had a lot of other ideas; I think we all did, but we went into it with an experimental approach, trying not to put too much pressure on ourselves and each other, leaving a lot of room for our own ideas and personalities to emerge.

Now that it’s finished I have some ideas that I hope it will convey: We love music – all kinds of music, especially music from and influenced by New Orleans. We like to groove. We like to play. We like to be dynamic. We like to have fun and feel free. We like to listen to each other and converse and weave and react and serve the song. We like to learn and improve, to improvise, to create something that is more than the sum of its parts, to be ourselves, to take risks. And perhaps most importantly, we want to share all of this with other people.

A lot of the music stems from guitarist Alexander Mallet’s writing, but the record still feels like a true ensemble. What’s the secret to keeping everyone’s voice present while holding onto the chemistry you’ve built together?

Yes, indeed! I’m not sure it’s a secret, but someone once told me that a famous comedy improv trope is to never say “no” during an act. Instead, say “yes, and…” when you’re feeling like going in a different direction. I’ve experimented with this idea a lot while leading the band, and playing in other people’s bands, and have shared this idea many times with Captain Buckles.

We’re still fine-tuning it and working on it and ourselves to varying degrees of success and effort, but there is no doubt in my heart and mind that this is the most prominent reason for keeping our voices present while holding onto our chemistry. The way we communicate now both musically and verbally is exponentially more supportive and trusting of each other than when we first started playing with each other a year or two ago in this configuration.

It’s a vibe, and it’s great. We hardly tell each other what to do anymore, it just kinda happens this way or that, and we either roll with it or go in a different direction, or try it both ways and see which way we like it more. Despite that, you never know what will happen in the next moment. Playing music together and spending time together on and off stage is so complex, with so much humanity and such a variance of emotion, that I never take these moments for granted nor do I expect it to always be such a great vibe.

Maybe the “secret” is to always strive for creating a space and finding the breadth within ourselves for each other and the music to be and happen without placing too much pressure or expectation for it to do so in the ways we want. That’s a lot of consistent work! I’m really grateful for the opportunity to work so hard at it with such amazing people and musicians.

Recording at Dockside Studio, with its storied past, what opportunities did it give you to experiment with sound, arrangements, or textures on the album?

Phil Breen, one of our keyboard players, said the piano there “sounds like magic”. I thought it sounded pretty great, but my inexperience in the studio made it difficult to appreciate it in its fullness. Although I’ve recorded in a bunch of different settings, this was my first time as a bandleader and producer/co-producer of a full-length album, and as such I was more focused on the vibe and keeping the session moving forward and going strong as a group than experimenting with sounds.

During the session, I definitely heard Phil, Rob, and Alex talking about how great all the gear in there sounded in more technical terms. post-production, many people told me that the drums in there sound just absolutely amazing. Justin Tocket, the house engineer, was quite the wizard in giving us the permission and freedom to try things our way. His expertise in handling our personal quirks and leanings, his technical ability in swiftly executing and interpreting our horde of requests, and his deep experience working with others was a huge contributing factor in the album’s success. We had a lot of confidence in him, and he treated us not as a fledgling band but as real musicians. That was a palpable feeling that I felt and was and still am grateful for, and we definitely tried a lot of different arrangements and sounds and textures spurred by this feeling and sometimes with his suggestions.

The property the studio is built on was also a huge factor. It was so nice to have so much room and to be so far from the city that we gig at. The property is huge and open, and being able to kick a soccer ball around during breaks or take walks outside and cook and gaze upon the stream in the backyard was just fantastic! Seeing framed records or CDs hanging on the various walls signed by B.B. King or Bruce Springstein, addressed to the studio, was inspiring, too, without being intimidating. It all just felt so right.

The music swings with steady grooves, yet it retains a loose, rebellious spark. How conscious are you of striking that balance between tight pocket and spontaneity?

I can’t speak for the rest of the band, but I definitely vary a lot with how conscious I am of striking that balance. It’s one of those things that really suffers when you overthink it, but is really important to practice. It has a huge potential to constantly shift with how other people in the band are playing and feeling at any given moment for any particular section. One comment or thought can throw it all into another zone! One of the things that I find most helpful is to just listen. Listening to what’s going on and having confidence in my ability to let go of my thoughts and be a conduit rarely leads to regret.

When I’m listening to others play their instruments and how it fits in the tapestry of the song, I’m often not capable of thinking as much and the voice inside my head can cease in these moments. Feeling and knowing when the next section hits comes more naturally in these moments, and what to do becomes more of a textural creative endeavor than a forced idea. It’s elusive, and maintaining that is difficult, but I try. To do so in a group setting where we’re self-producing and running the session among ourselves adds a very complex layer to it, but I think our shared focus on this and our desire to serve the songs and music and the feeling of trust between each other really made it easier and possible to largely stay in that flow state.

The album is mostly instrumental, with some awesome vocal moments as in “Bus Station Blues” and “Raindrops on Mardi Gras.” What does leaving that much space in the music let you communicate without words?

Yeah! Rob really laid down some great vocals, indeed! I always liked his singing and approach, but when he re-recorded them at Esplanade Studios, he really took it to another level. Having a lot of non-vocal space in music is tricky. There are so many times where it can feel like “not enough is going on.” There are so many examples that come to mind of instrumentals that are on the verge, or too busy, or a gazillion other things. Booker T & the MGs was the first huge influence on me as a bassist. King Curtis was one of the first guys I heard that did instrumental versions of vocal songs that sounded pretty great and that I recognized. The Meters were the kings of funk when I discovered them but I could rarely hum a melody, let alone identify one back then. The list goes on.

I think a lot of it has to do with intent. And personal taste and satisfaction with what’s going on. And ability to actually hear and listen to what’s going on. I played bass in rock bands with vocals in them for maybe a decade before I actually had the capacity to listen to the lyrics without screwing up the bass part. I know tons of musicians like that — in fact, I still get in my head about things sometimes and can’t “hear” certain things, for sure — but our listening experiences are so varied.

For a few years now I’ve been experimenting with the idea that if you’ve got a deep and consistent enough groove, you can do anything. Anything will sound good and sound like “enough” is going on. Then it becomes more of a choice of how it feels, and what you want to say, and what you want to evoke: feelings, textures, landscapes, etc… And sometimes it can just cascade out of you, or the musicians in the band, or a chain reaction starts happening.

With the right kind of mindset, patience, listening ability, and technical ability on whatever instrument you’re contributing on, the sonic landscape is limited only by where everyone can come together, and the groove is one of the easiest places for that!

This album was funded in part through a Threadhead Cultural Foundation grant. Did that kind of community support influence how you approached the record or what it means now that it’s finished?

The Threadhead Cultural Foundation made this all possible. Without their help, we definitely wouldn’t have been able to afford to get out of the city for three days like we did. Even more so, some key members like Doug Kosydar and Dan Ring really encouraged us to apply for the grant, and really affirmed my belief in the possibility that there are people out there that want to hear us do our thing, that there’s something worth working hard for. Our only somewhat-local festival performance at the Wild Things Family Reunion in 2023 was where we got to play for them for the first time, and that opportunity was made possible with the support of Marc Paradis of Johnny Sketch and the Dirty Notes. He gave us our first chance, and it was such an important step.

Prior to that, we’ve played mostly to tourists in bars in New Orleans. You can get away with doing some original songs, but mostly people want to hear stuff they know when they’re drinking and looking for entertainment, and even though we would often get a couple or a handful of people each show telling us how much they dug our vibe and original songs, their feedback never really hit the way Doug and Dan’s feedback hit, for me. I mean, these are guys that get George Porter Jr. of the Meters to play their Patry every year, so for them to continue to cheer us on means a lot!

There are others, too, but I want to make it clear that their specific kind of community support was imperative in giving us the confidence to try to put out a record the way we did. To be our best selves, to be comfortable and not try to consciously imitate anybody, to do it on our terms and do original music, to experiment, and more. That kind of confidence has been so elusive! The band and I have played so many shows under other people’s names. Most of us have formed our own bands before, and stopped for various reasons.

Tribute bands are touring the nation. Cover bands are getting paid the big bucks, sans the superstars and superbands that are already established or are social media-famous. We’ve all played in quite a few working bar bands locally in New Orleans where alcoholism is rampant and a crutch. I doubt I speak for only myself when I say that I’m eternally grateful for their help, for this opportunity to make a record like this, and in this regard I feel very truly successful in accomplishing it together with everyone. It can be said that this album is a love letter to New Orleans, to each other, to the music we love, to the people who helped make it happen.

If someone hits play on Hurry Up having never stepped foot in New Orleans, what do you hope they understand—not just about the music, but about the city’s spirit?

New Orleans is truly a place where one can be themselves. It has been, for ages, and continues to be that for many. Although it’s increasingly hard to find oneself in this over-personalized, over-polarized and fast-paced digital age, it’s still possible. Risks are still worth taking, courage should be celebrated, and it takes at least both to find a sense of community and belonging for most people.

I hope that Hurry Up is a testament to these things, and more. The music and grooves of New Orleans has inundated the world many times over, and it’s no coincidence! This city’s spirit is full of soul, is full of triumph over suffering, is full of celebration. We all need more of all of that.