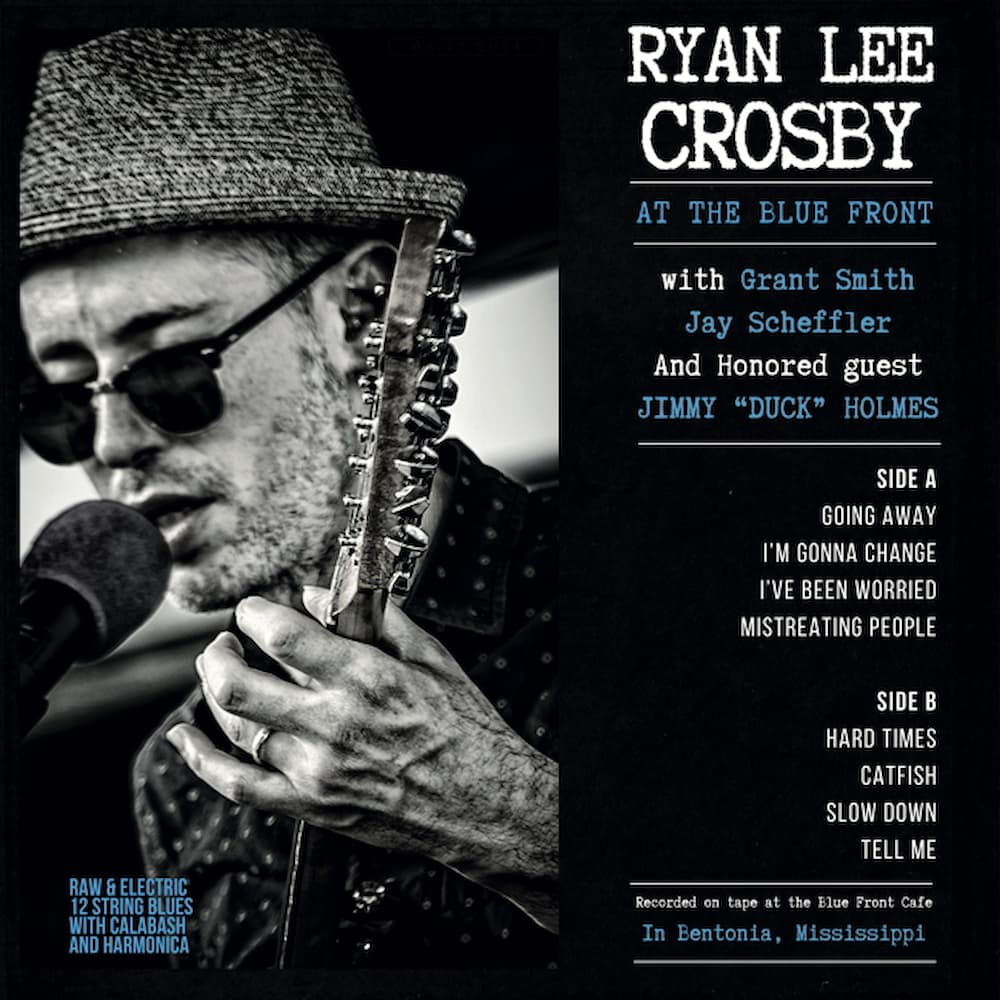

When Ryan Lee Crosby plays, his music doesn’t just summon the ghosts of Delta blues — he communes with them. On “I’ve Been Worried,” premiering exclusively on American Blues Scene, the Portsmouth, RI guitarist brings a haunting immediacy to the Bentonia tradition. The track was recorded live to tape at the legendary Blue Front Cafe — the oldest surviving juke joint in Mississippi, which is still run by Crosby’s mentor and collaborator Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, and once played by blues greats like Skip James.

In support of his new album, At the Blue Front, we caught up with Crosby about the process of translating a living, breathing juke joint into a record. As he puts it: “The qualities that are in this album express a lot of what I value in playing, composing, teaching, and production. Make it true, make it real. Create with presence and love and attention and focus. Be Spontaneous. Listen. Keep on growing; keep on going.”

Jimmy, the last living link to the Bentonia blues lineage, joins him on the latter half of album. But their bond runs deeper than influence. “When I play behind Jimmy, I’m completely organized around listening,” Crosby explains. “And when I was singing, he was locked in to everything I said and played. He led and followed.”

For listeners experiencing At The Blue Front for the first time, what emotions or reflections do you hope the album and this video evoke?

A sense of care, of reverence, of appreciation, love and commitment. I hope listeners can hear the sound of people really listening to each other and that they can feel the relationships between the players.

Recording at the Blue Front juke joint is a huge part of the album’s identity. Can you share what it felt like to capture your music in such a historic space where legends like Skip James once performed?

I believe you can feel the weight of history, as well as the presence of Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, the moment you walk into the Blue Front. Decades of culture and legendary music loom in the air. And you feel those vibrations when playing in the space. The sounds you create mingle with the echoes of those who have been there, the original blues musicians whose essences continue to reverberate. All of this, I believe, was present during the recording and perceiving it brought an immediacy to the process. It drew us right in, beyond analytical thinking, to a deep place of feeling, to a delicate balance of focus and receptivity. I hope this comes through to the listener.

Your playing on the 12-string guitar is truly distinctive. How did you develop your unique style on the instrument, and what drew you to the 12-string specifically within the blues tradition?

I was first drawn to the 12 string by Robbie Basho and some of the work he did on Takoma Records, which is connected to Skip James through John Fahey. Before I had a 12 string of my own, I had a Robert Pete Williams album that he played some 12 string on and that spoke to me. But it wasn’t until I heard Robbie Basho that I got one of my own and once I tuned it down two steps from standard (to approximate Lead Belly’s sound), I realized that it was an instrument where all of my inspirations and influences – from Mississippi blues to Indian Raga to Kora music – could live in harmony.

Most of my blues influences are six string players: Skip James, Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, Robert Belfour, Jessie Mae Hemphill, RL Boyce, and John Lee Hooker are a few of my favorites… as well as Malian guitarist Boubacar Traoré. My approach to the 12 string is to play in a way that feels true to my heart… and the musicians who inspire and influence me have all illuminated the path home to myself.

Jimmy “Duck” Holmes has been a crucial mentor for you. What are some of the most important lessons or moments you’ve shared with him, especially during the recording process?

Be true to yourself and be true to the music. When you record, you are documenting a moment, that’s all. Capture the moment as purely as possible, as close to the original creative impulse as you can. Don’t critique the work as you go. Just play. A sense of play is important in all stages of the creative process.

Beyond recording, there have been countless important lessons from Jimmy – some of these lessons have been technical instructions, others have been impressions. Jimmy has helped me learn to play and listen beyond the bar line – to think in terms of cycles and pulses, one note at a time, one beat at a time. All my life I have searched for freedom in music. I found it first in punk and post-punk rock, now I hear it in Jimmy’s playing and I channel my experiences with him into my own work. The shows I’ve been playing since making the record have gotten freer and freer, which in part is possible because my partner Grant Smith is an exceptional listener and improviser. Jimmy has told me “never play it the same way twice,” which makes a lot of sense to me. Do we live every day as if it’s the same or do we live each day, each moment, with a sense of newness? Music is an expression of life and it follows nature’s law. So it makes good, natural sense that the rendering of a song will be new every time you play it. This is a process of listening to how you feel when playing. It’s important to take your time, don’t rush it. Let the feeling come to you and through you.

Something I’ve realized in Bentonia is that, for me, the learning of a song note for note and always playing it that way is kind of like learning a soliloquy or a monologue… but people speak to each other in conversation and a conversation happens in a moment, it is never the same way twice. The playing of music with people, for people, or for a tape recorder and for the spirits in the room is in essence to participate in a conversation. And, I suppose one could recite a soliloquy in a conversation, but it’s not natural and likely to be removed from what’s unfolding.

Jimmy has also impressed me with the importance of always telling the truth – in your playing, in your writing, in living. And more and more I try to apply this to all aspects of life – to just be true to the moment and watch it all unfold. To let whatever that wants to come through, to come through.

Bentonia blues carries a certain mysticism and emotional depth. How do you approach keeping that spirit alive while also bringing your own voice and innovation to the style?

I agree that the blues carries a certain mysticism and emotional depth. There are many deep, emotional and mystical kinds of music, but the Blues has its own mood and essence. I feel that the Bentonia Blues in particular offers a doorway into a particular kind of atmosphere and experience. Words like “ethereal” and “otherworldly” are often used to describe it and I would say, rightly so. I have personally been interested in ghosts and spirits for a long time – music is a portal that engages us with the invisible and if we are paying attention, music can help us see and hear finer vibrations and energies, if we are willing and able to recognize them. Music itself is energy and certain keys, chords and combinations of notes can be especially potent. The Bentonia Blues is one example. If you listen to it and pay attention to your feelings – where does it take you? What emotions and thoughts arise? The responses we have to music originate inside us, they come from the invisible and can be mystical in nature.

Part of the mysticism of music is its ability to live on forever. We are still feeling the music of Skip James now in 2025, from recordings he made in 1931. The echoes of this music are vibrations that hang in the air, which we can still feel. Here we are discussing it now. And when we put on any of his recordings, we have the unique privilege of traveling back in time to the moment when he made them. It is a miracle. Those moments live on.

I believe that the spirit of the blues will never die as long as humanity exists, because it is the song of the human experience. All people can relate to it, regardless of who you are and where you come from. I don’t personally try to keep the spirit of the Blues alive, I just love the music and want to honor it, as well as the people I’ve met through it. And as long as Jimmy “Duck” Holmes is here, then the Bentonia blues is still here. He keeps it alive because he lives and breathes it every day. And there are people around him who help and support the work. I am glad to be one of those people, if I can… and I do try to be. How can I not, after all the ways he has supported me?

As for the second part of the question, I do, however, think more and more about bringing my own voice to the music, because although I feel I know my own voice and have for a long time, I have spent the last ten years trying to learn the music as true to the tradition as I am able to perceive, given that I am coming to it from the outside. My intention has been to study as closely as I can, to give back at least as much as I receive and to hopefully do no harm in the process. Making these recordings with Jimmy feels like a phase of completion (although the study of the music is a lifelong process) and now I’m becoming increasingly interested in drawing from all the areas of music that speak to me.

Since completing At the Blue Front (as well as having also produced and played on Jimmy’s upcoming album Bentonia Blues / Right Now), I have become increasingly interested in writing and singing from my own life, as well as drawing from all the music that inspires me, especially music that might seem on the surface to be outside the blues tradition. I am interested in further clarifying my own ideas of what it means to be an artist and reconciling the part of my musical life from before I started going to Mississippi with what I have learned along the way.

All my life, I have wanted to be a blues musician, but I think what really makes an interesting artist to be one’s self truly and thoroughly. To be able to see the world through your own lens and express it fully, rather than trying to fit one’s self and one’s creativity into a box. I’m not from Bentonia and could never try to be. I think what I have to offer exists within this truth.

The collaboration on the latter half of the album often ventures into improvisation. Can you talk about what that creative exchange with Jimmy “Duck” Holmes looks and feels like?

It feels, to me, like absolute presence and total alignment. It is an act of listening, receiving, responding and supporting. And all of this is a two lane street. When I play behind Jimmy, I’m completely organized around listening to every word he sings, every note he plays and the spaces in between his phrases. I am there to participate in musical dialogue with him.

For years, whenever I’ve played with Jimmy, my intention has been to follow… but on the making of these recordings – both his new album and mine – we took turns passing the microphone back and forth and I realized then that when I was singing, he was locked in to everything I said and played. It wasn’t just a matter of following him all the time. He was gracious, present and supportive. He led and followed. And even when he was following me, he was leading by his example of how to do things.

In the sessions, there was never any discussion of how to play or sing or do anything. It was all completely nonverbal and after the song was over, we moved on to the next one. All of the songs we did together are first takes. “No rehearsals, that’s how the old man does it,” is what Jimmy said to me. All we did was I set up the tape machine, the microphones and preamps, and we started to play. We played a few hours in the afternoon for two days and got two albums out of it. “That’s how the old man does it.”

You’ve been called “a young torchbearer of the style” by Smithsonian Magazine. How do you personally understand your role within this tradition?

All I really think about is my connection to Jimmy and to the community. I understand that I have been given a great gift in having these experiences and connections in Bentonia and in the south. I want to be true, to walk a path of decency and to give back more than I get, in any way that I can. I think of my playing of the Bentonia style as the expression of a relationship, as “this is what I have learned from the man who showed me,” as well as an expression of who I am in how I have processed it. I hope to honor Jimmy and his generosity in my playing. And I want to take this forward for the rest of my life.

How do you integrate such diverse inspirations into a cohesive sound that’s authentically yours?

All I want to do is be myself. When it comes to Blues influences, I don’t play anything that I didn’t learn from a human being directly. And this keeps me true to my own experience. I was lucky to play, travel and record with RL Boyce on and off in the last year of his life. Paul Rishell introduced me to the music of Skip James, which prepared me for learning from Jimmy “Duck” Holmes.

I was fortunate to have a number of lessons with Indian classical slide guitar guru Pandit Debashish Bhattacharya and to study raga with Warren Senders in Boston for a couple of years. The South African guitar virtuoso Derek Gripper introduced me to aspects of Boubacar Traoré’s music. I connected with all of these teachers because I loved their music and because I had a yearning in my heart to find out more about each of these traditions, in which I could feel an overlapping emotional resonance. And I’ve always wanted to stay true to my own heart. So, I just keep on going and trust that all of these influences and experiences will continue to mature into who I am meant to be.

The blues is often described as a living conversation between past, present, and future. How do you experience that conversation in your music and your life?

I often think about where the music comes from and why, both on cultural levels and on a personal level. I try to consider the unimaginable conditions that the originators of the music had and have to experience, as well as my own personal motivations, including what circumstances in my life led me here and where I feel it might go next. I also think about lineage, what it means to hold truths that are given to you and to pass them on.

For me, nowhere I’ve been embodies this more than the Blue Front Cafe, a living juke joint that has been open since the ‘40s, where musicians like Skip James, Jack Owens and Sonny Boy Williamson II all played, and where musicians of today from all over Mississippi and beyond put on live shows with Jimmy “Duck” Holmes every week, with no signs of slowing down. In addition to performances, Jimmy also teaches out of the Blue Front, with people coming from near and far to learn from him.

We’ve begun an annual tradition in which I bring my own guitar students down to learn from him directly, which we do in April, just a couple of days before the Juke Joint Festival in Clarksdale. And Jimmy’s own Bentonia Blues Festival is one of the longest running local Blues festivals in Mississippi, going back to the ’70s. I’ve been playing the fest since 2019 and it gets bigger every year. So I see something of the future in this as well.