A GRAMMY at 18 seems like an impossible feat for most, but that’s reality for Nashville’s young phenomenon Yates McKendree. Fate dealt McKendree a musical hand, and he’s playing it with skill, style and soul.

McKendree is a singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and engineer whose rich, soulful take on the blues is full of the nuances made famous by B.B. King, Otis Rush, and their spirited counterparts. His guitar work is finessed and full of ’60s soul man sounds only a true obsessive could capture, while his powerful vocals take a detour through the heart before they reach the mic. McKendree is changing the landscape of modern blues while keeping the legacy of the old-school stuff alive.

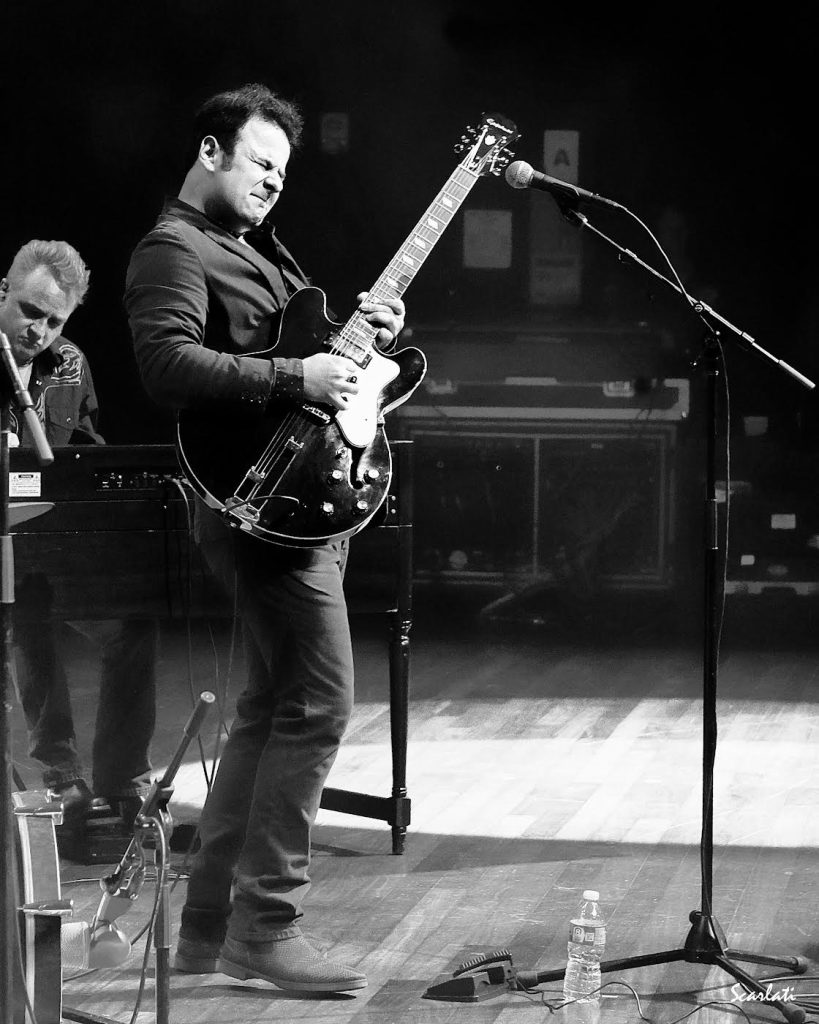

Yates performing at The Ryman opening for Brian Setzer

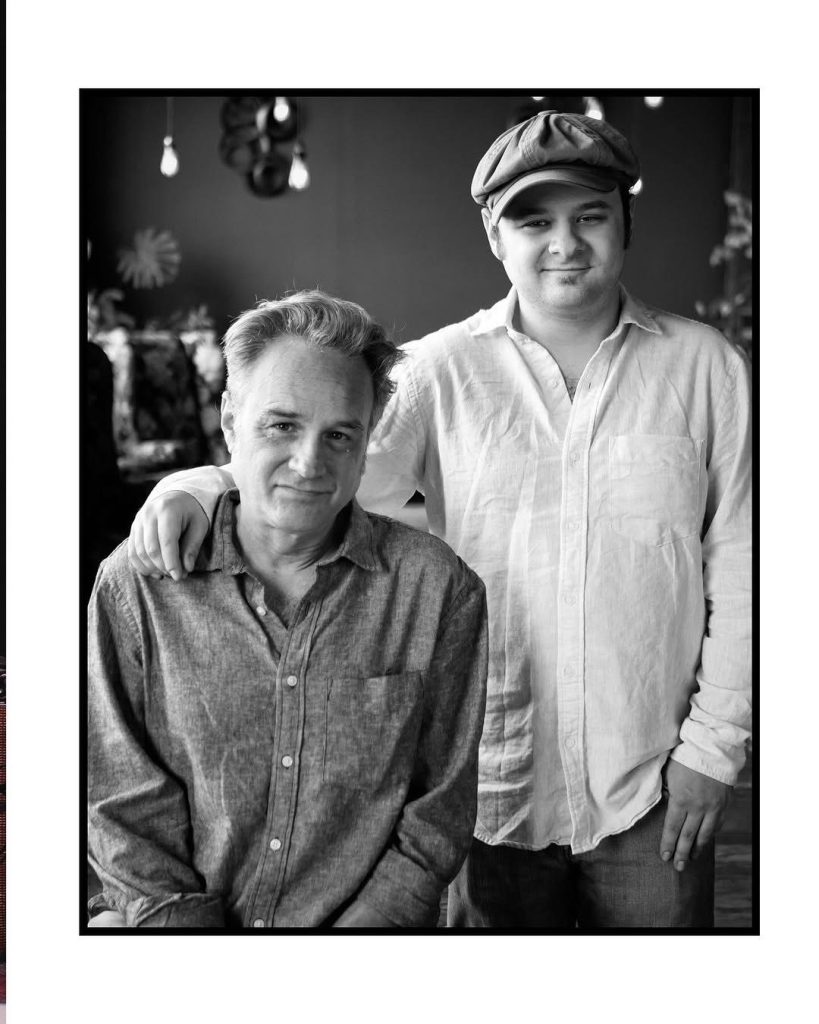

For the McKendree family, the blues are part of their DNA. Growing up in a musical household, his father Kevin McKendree, a respected keyboardist who has played alongside Buddy Guy, Little Richard, and Delbert McClinton, among others, filled their home with the best of American music.

“Some of my earliest memories are being in my dad’s Toyota Four Runner and as a toddler we would ride around and listen to two songs in particular: ‘Going Down’ by Freddie King and ‘Tilt-A-Whirl’ by Jimmie Vaughan. That’s a core memory for me. Growing up surrounded by music, especially blues and roots and soul, it’s impacted me more than I can even describe,” Yates reminisces.

The impact was so fierce that it inspired a young Yates to explore multiple instruments before he’d even mastered the English language. “I got my first drum kit on my third birthday, so that was my first instrument. I also started fiddling around on the piano at three as well, and then picked up guitar at six. I’m completely self taught and I used to play guitar in my lap because my hands were too small to fit over the fretboard, so I’d play with my thumb. I did that for years until I was about 14 or 15,” he says.

Guitar soon became McKendree’s superpower. Channeling his feelings through the strings is his strongest feat as a performer, and it was the influence of his blues forefathers that helped him find his own sound. “Freddie King was my biggest hero of all time, and still pretty much is. But I remember I got a hold of my dad’s iPod when I was nine or ten, and of course it was loaded with really great stuff. I stumbled on ‘Mourning in the Morning’ by Otis Rush, and immediately I was obsessed. Otis is a huge influence on me too. And of course I adore B.B. King; there’s a live record that in my opinion is the greatest live record ever called Blues Is King. That’s another one I discovered early on. But of course T-Bone Walker, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, Guitar Slim – they all have a part in what I do.”

His appreciation for those who came before him hasn’t gone unnoticed. After one of his regular Monday night shows at the legendary Bluebird Cafe, modern country legend Chris Stapleton stopped him backstage and told him how thankful he was that Yates was keeping Blue Monday alive after the passing of Chicago bluesman Mike Henderson, a moment McKendree still recalls with disbelief. “I grew up watching Chris at a small local club with the Steeldrivers before they were famous. Chris came up to me out back at the Bluebird a couple of months ago, and told me how thankful he was for me to be carrying on the Blue Monday tradition. It meant so damn much… I definitely hope to write with him in the future.”

Mckendree’s second album, Need To Know, dropped in July, and it’s a record that deepens his sound without losing that vintage pulse. “The original stuff I wrote with a really dear friend of mine, Gary Nicholson, who’s written for tons of people like Ray Charles, and B.B. King. I’d go over to his place, we’d sit down, have a cup of coffee and talk about life with guitars in our laps. When it comes to the recording process, for me there’s something about just cutting it live in a room with a band and that’s what we did. We did two or three takes and moved on to the next song. It’s a bunch of people in a room just playing with each other, looking at each other, and feeling it out. There’s a beauty about it but not a lot of musicians choose to do it anymore. It’s pretty old school.”

Like the blues itself, his inspiration comes straight from life. “That’s what it’s about, your life experience, what you’ve been through, what you feel. The blues is a personal thing, an emotional form of music. Heartbreak is obviously a big theme. Just real life situations.”

Asked to pick a favorite song on the album, McKendree doesn’t hesitate. “I really love how the cover of the James Brown tune I Don’t Care came out. I love that song, and there was just a specific energy in the room when we cut it that gave me chills, so that’s probably my favorite track.”

The album is full of standout moments, including “Need To Know You Better,” a song so classic sounding it’s easy to mistake for a cover. “I wanted to take more of a soul blues approach with this record,” he says. “My first album Buchanan Lane was more traditional, which I love, but I have a love for so many different types of music. I wanted it to be different but still in the same vein as the first record.”

He resists labels when it comes to describing his sound. “American roots music,” he says after a pause. “I don’t want to box myself in, because I listen to jazz, soul, funk, R&B… even though the blues is my greatest love in life, that’s not strictly my sound. It’s an amalgamation of so many different things.”

McKendree’s father, Kevin, also produces his work and plays alongside him. “Growing up I always heard him playing piano. There’s no weirdness there, we get along great, and he’s the best piano player I’ve ever heard,” Yates laughs. “The best advice he’s ever given me? Be yourself, be kind, be humble, don’t give up. Keep pushing.”

Those words stuck with McKendree and before long a GRAMMY came his way “On top of being a musician, I’m also an audio engineer, and I was the engineer on

Delbert McClinton’s Tall, Dark and Handsome,” he recalls. “When I found out we won the GRAMMY, it was absolutely insane. I was gigging in New York at the time, and we’d just finished a show. I was sitting in my hotel room with a couple of friends and got a text that said ‘WE WON!’ It was surreal.”

That moment was a reminder that he’s exactly where he’s meant to be. “It’s one of my greatest honors to carry the torch forward,” he says. “Just growing up around it, my dad started playing blues when he was 18 too. He’s played with a ton of people like Buddy Guy, Earl King, James ‘Thunderbird’ Davis, Johnny Taylor, Carey Bell, Eddie Kirkland, and he was Delbert McClinton’s bandleader for close to 30 years. So it’s absolutely in my blood.”

As for what’s next, McKendree keeps his goals grounded and real. “One person who I adore and would love to work with is Lee Fields,” he says. “And I’d love to be in a place where I’m playing big festivals and theatres. My whole thing is, I just want to make a comfortable living doing this. If I can do that, I’ve got it made.”

When asked why the blues, his answer is simple: “The blues means everything to me. The blues is life. It’s the truth. There’s nothing that hits me more emotionally, in my heart and in my soul, than the blues. There just isn’t.”

That truth has been evident since childhood. He still remembers the day a stretch limo pulled into his backyard carrying none other than Little Richard. “I was about nine or ten, and one of my dad’s old friends, Kelvin Holly, he was a longtime member of Little Richard’s band, was working on a tribute record for Solomon Burke. Richard wanted to be part of it, so Kelvin convinced him to come and track at our place,” he recalls.

“I remember just being in my room, and suddenly this limo pulls up. Out comes Richard, he wasn’t doing too well at that point, he was in a wheelchair, and he had a whole security detail with him. Two huge dudes guarding the studio doors. It was wild.”

Young Yates couldn’t help but sneak in a recording, despite the “no filming” rule. “Richard noticed and pointed at me and said, ‘It’s okay, you can film.’ Then I got to sit down and play some boogie woogie piano for him, and he was smiling next to me. After I finished, he gave me the nickname ‘Piano Boy.’ It was surreal. Definitely a core memory.”

The most incredible part? That session was never released. “It’s somewhere on a hard drive,” McKendree says, “we literally have Little Richard’s final ever session, completely unreleased.”

It’s the kind of story that sums up McKendree’s life perfectly: steeped in music history, touched by fate, and guided by the power of the blues.