I have listened to and studied as many of the great guitarists as I could wrap my hands and brain around. I have met a good number of them. I’ve even performed with several. There is but one, however, that I ever wrote a song about.

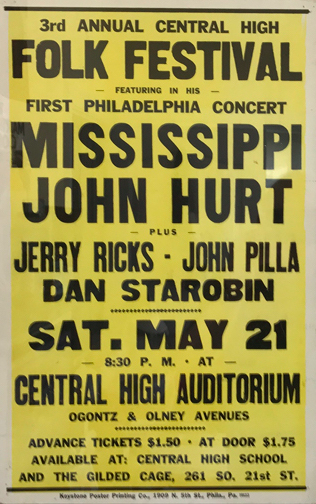

Mississippi John Hurt‘s first go-round with the music business came crashing down in 1929. He got another chance at the age of 71. But then he was cruelly exploited by his management. That changed on May 21, 1966 backstage at a show at Central High School in Philadelphia, PA.

From my perspective, the best part of the “Folk Music Revival” of the early 1960s was the spate of rediscovery. A number of musicians, scholars, and collectors fanned out searching for artists they knew only from recordings on 78 rpm discs made decades earlier. Artists, both black and white, were found in varying degrees of health and retained musical proficiency. These included Son House, Clarence “Tom” Ashley, Dock Boggs, Skip James, Blind Willie McTell, and Furry Lewis.

The most instantly popular and, I would think influential, was Mississippi John Hurt. He had done two sessions, in Memphis and then New York, for Okeh records in 1928 and 1929 but continued through the depression and the intervening years to labor about his home in Avalon, Mississippi. He was represented by two songs included in the legendary Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music, which came out on Smithsonian Folkways in 1952 and was the master text for the young enthusiasts who would form the core of that revival.

He was found in 1963, when Dick Spottswood and Tom Hoskins (AKA “Fang”) took at face value his lyric, “Avalon’s my hometown, always on my mind.” And indeed it was.

If you haven’t had the pleasure, it is difficult to describe Hurt’s music and his presence. More a “songster” than a bluesman, he played a mixture of popular songs, traditional numbers and blues tunes, syncopating with a light touch over a strong 4/4 backbeat with his thumb. His voice, deepened with age, was warm and mellow.

As to his presence, I call him the Buddha figure of the folk scene. I’ve always said that he could have come out without a guitar and sat down and laughed and told stories (in an accent perhaps difficult for Northern audiences) for 25 minutes and never provoked a request for a refund.

You can get a wee taste of that on the Folkways release of The Friends of the Old Time Music concerts. (Ralph Rinzler, John Cohen, Irwin Silber, Mike Seeger and others, organized to bring traditional musicians to New York.) Hurt played on a bill with Dock Boggs on Dec. 13, 1963. He starts out talking over some idle guitar strumming and says, “I’ve been back with you all once again. The reason I say that, in ’28 and ’29 I recorded for the Okeh company and I haven’t had a chance to be back to New York until tonight, and I feel kind of like… I’m at home.” He chuckles and gets a long round of applause and breaks into “Creole Belle.” He’s got them city slickers eating out of his hand before he sings a note.

In addition to any and all of his recordings (the studio sessions on Vanguard are the best for fidelity) I can recommend his appearance on Pete Seeger’s Rainbow Quest show for what was then called educational TV, circa 1965.

Dick Waterman (d. 2024) was John Hurt’s manager from May, 1966 for the rest of his life, which, sad to say, turned out to be but six more months. He named his management company Avalon Productions. He was a 2000 inductee to the Blues Hall of Fame, as he told me, the first non artist, non-record-company-guy to be so honored. By the end of the ’60s, when I was doing college radio at WXPN-FM in West Philadelphia, Dick was living in town. (Half a block from Jerry Ricks [below] which was too strong a blues connection to be a coincidence, although never explained to me.)

Dick used to call me at the station while a record was spinning with comments and suggestions. That was the beginning of a friendship that lasted through the decades. One where I was involved with various projects with his artists. Occasionally as a musician, but more often filling needs in presenting, production, promotion, or logistics. Each one of those is a different story (or more,) but the artists include Mississippi Fred McDowell, Bonnie Raitt, Robert Pete Williams, Son House, Skip James, and Buddy Guy.

Jerry Ricks was my guitar teacher from 1964 to 1966, a period I laughingly refer to as “high school.” Of the Afro-American persuasion, he was raised in West Philly and in the 1960s was the hippest folk guitar teacher in town. And Philly was a hip folk music town. Averaging over two tunes a week, we covered (as he said decades later) all the John Hurt tunes and all the Doc Watson tunes. And also a broad and deep survey of pretty much everyone who contributed to the body of blues, country, and folk guitar.

His personal relationships with Mississippi John Hurt and Doc Watson were my entry to the dressing room when they played the 2nd Fret, Philadelphia’s legendary folk club at 1902 Sansom St. That may have been the deepest lesson of all, that the action was not the stage and the front of the house; certainly a life-changing experience for me – hanging out in Mississippi John Hurt’s dressing room.

In 1969, Dick Waterman sent Jerry to Africa to road-manage the Junior Wells/Buddy Guy State Department tour. Jerry recorded with John Hurt and can be seen, as the camera zooms over his shoulder, playing second guitar with Son House on the Camera 3 TV show from early 1969. (The internet seems to assume that it’s Buddy Guy in that shot, as the show ended with a memorable Guy/House duet, after a half hour of alternating House solos and Guy quintet numbers, but it is definitely Jerry Ricks. That’s Jerry’s D-18 Martin that Buddy plays in that last duet.)

Ralph Rinzler sent Jerry to Arkansas with the Texas folklorist Mack McCormick to research musical programs for the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife. Around 1971, Jerry moved his family to Europe, residing variously in Germany, Italy, and Croatia. There he built a performing career as the fedora-sporting “Philadelphia Jerry Ricks,” John Hurt resonances intentional.

I never knew Hoskins or Dick Spottswood, although when in the DC area I looked forward to Spottswood’s radio shows. It is my understanding that Hoskins took management and Spottswood did the record company. This is covered in detail in the book Mississippi John Hurt: His Life, His Times, His Blues by Philip R. Ratcliffe; University Press of Mississippi, 2011. While I enjoyed and learned much from that well researched book, I hit a disconnect when it came to that Central High School show and the confrontation between Hoskins and Waterman. I was at the show.

Jerry Ricks and John Pilla (who went on to record with Doc Watson and record, tour, and produce with Arlo Guthrie) were also on the bill with Dan Starobin opening. Danny (another Jerry Ricks student) had graduated Central the year before. With his 10-piece band, Sweet Stavin’ Chain, he had a regional hit with a psychedelic version of the Teddy Bear’s Picnic, circa 1970. I stayed out in the audience that night at Central, Jerry saying there were too many friends and students there to bring backstage.

Philip Ratcliffe seems to draw most of his account of that backstage scene from Jerry Ricks, who passed in 2007. Hoskins died in 2002, although his sister gets quoted. Whenever it was that Jerry spoke to the biographer, he comes across much less angry, and the exploitation is not described as severely as when he told it to me at my guitar lesson on Wed., May 25, 1966 — four days after the fact.

Ratcliffe did not talk to Dick Waterman, so after sitting on my questions for some time, I did. The following is a transcription of the recording I made, with permission, of that conversation. Unfortunately it both starts and ends abruptly.

An Oral History with Dick Waterman (March 26, 2018)

DW: What happened is that John’s niece at that moment to know the facts of how Tom got John’s…

TE: Right.

DW: She had built up a real anger, just an absolute anger.

TE: Uh huh.

DW: So what happened is there was John and Tom, Jerry, and the niece standing there when I walked in; and Tom made some remark about, “You have no business being here.”

Then she commented, “No, you got no business, here. You’ve been cheating my uncle.”

John cringed back at this. He wanted everybody to love everybody.

TE: Yeah.

DW: So, ah, he cringed back on this and I said, “Look Tom, you’re through. Let’s just take a hint and get the fuck out of here.”

And I think that’s how it went down and he swore that the courts would avenge him and that he would be validated.

I don’t think he anticipated being the first to die, which he died several years ago. I understand that he died broke in a Florida hotel room.

TE: Um hmmm.

DW: Yeah, and that was it. He swore he would get revenge and left. That was it, no more than that.

TE: Huh, he never did sue, though?

DW: What?

TE: He never did sue you or John.

DW: No, oh no. Not at all,

TE: No.

DW: In order to do that, he would’ve had to have brought to light the management contract.

TE: Right.

DW: See, when they were arguing whether John had the right to be recorded by Vanguard—and the management contract was brought out by Hoskins. So that he had a valid legal right to control John’s recording and Vanguard did not.

And the judge who looked at it said, “The validity of this contract is not to be argued here. We’re only arguing whether Vanguard had the right to record John Hurt, which they did not. So therefore, I find in favor of Music Research, [Hoskins, Spottswood and ED Denson] although in fact, this contract is one of the most heinous, high-footed, abusive, ‘offenses that I have ever seen.’ But that is not the business before this court at this time.”

So, we at least did get a judge to give an opinion on the validity of the contract. But that validity of the contract was never argued in front of the lawyer, or judge.

TE: What was the niece’s name, by the way?

DW: What?

TE: What was John’s niece’s name?

DW: I don’t know, but I know that she died young.

TE: Okay.

DW: Her actions put a curse on all of them.

[DW confirms that he was not speaking of Hurt’s granddaughter Mary Francis Hurt, who runs the Mississippi John Hurt Foundation.]

TE: Jerry mentioned he’d spoken often with Dr. Ratcliffe, who wrote a book on John Hurt.

DW: I don’t know, where is he from?

TE: Scotland, I think. England somewhere.

DW: Yeah, that’s possible.

TE: Yeah I read the book, it’s been a couple of years. It didn’t seem like he had talked to you, but he had talked to Jerry.

And Jerry told that, you know, the showdown was at Central High School.

Now Jerry told me that week that, as Jerry would have said, “Fang and them” were taking like maybe two thirds of John’s fees.

And that John moved to Washington and then they told John that work was drying up and John moved back to Mississippi.

And they told everybody else that they were gonna book a farewell tour at even higher prices that they were gonna still take two thirds of and… book John on one last tour and clean up.

Then send him back to Mississippi with whatever they paid him.

DW: Well, I actually saw the contract once, and I saw it and it was front page and back page single spaced.

TE: Uh-huh.

DW: It was not a joy to read.

TE: Right.

DW: It was…They took 50 percent off the top of John’s money, period.

TE: OK.

DW: From John, they had the right of all publicity, promotion, advertising, opening act and all other accounts and expenses as they shall deem necessary.

TE: Um-hmm.

DW: So their taking two thirds is probably right about correct.

TE: OK.

They were taking the top half and then every expense was taken out of John’s half.

But I mean, there were people who knew. Sam Hood, who owned The Gaslight, knew. [d. September 3, 2007]

And the way he knew was because when John came to get paid, Hoskins was somewhere else and Hoskins came back just as Mr. Hood was counting 600-650-700-750 there’s your money for the week, John.

And John just looked down at it and was gobsmacked.

TE: Huh!

DW: He had no idea he was getting that much money. And Hoskins at that point knew that somebody knew…aaah…what John Hurt was receiving for a week’s pay.

So I don’t think Mr. Hood ever done anything, but Hoskins was like the little boy filling the dike with his finger, soon there were leaks all over the place.

People would know it, how much John was getting and it was a pitiful small amount of money.

I heard that John wanted to go back to the South because the kids were getting under the influence of gangs. Street gangs in Washington. There was a lot of violence out on the street.

And John held them dear and wanted them brought up in Mississippi.

Now, you can take that for what it’s worth, but I did hear that.

TE: Did you ever hear anything about a farewell tour they were trying to book?

DW: Oh no. No, no, no.

In other words… END TAPE.

Were I an actual skilled interviewer there’s a lot more questions I might have asked. It is both only fair and simply true to point out that Dick Waterman was pushing 83 years old on that day when I called out of the blue and said, “Tell me what went down with Fang at Central 50 years ago.”

Dick did confirm my understanding that as he added management to the concert booking he was already doing, he did not charge Hurt, although these activities did lead to Dick’s long career in artist management. He validated Jerry Ricks’ view of the contracted management share at two thirds, but had no information on some of the other points of exploitation Jerry had described in 1966, but apparently did not discuss with Philip Ratcliffe. I can’t think who else might be alive and could know about these things.

I did speak with Carl Apter, who was the president of the Central High Folk Club at the time and remains a major Mississippi John Hurt fan. He was busy with a show to run and did not witness any such confrontation. He does remember Hoskins asking him for half of Hurt’s pay, and as the show had been booked through Waterman and Ricks he refused. We have no way of knowing if that occurred after Fang had just been fired, although it seems odd if he only requested “his piece.”

John Hurt’s music, both on record and in my own renditions of his songs (such as they are) remains a steady source of joy and comfort in my life. Mississippi John Hurt, Dick Waterman, Philadelphia Jerry Ricks, John Pilla, and Danny Starobin are all gone now.

But I remember them and fondly–along with Doc Watson, the backbone of the Philadelphia blues and folk guitar scene of my youth. I was in near enough proximity as the events unfolded that the account in the biography demanded answers.

This article is about seeking to understand the tale of exploitation as carried in my memory. While I sort of get the biographer’s neutral stance — finding quotes with nice things to say about both antagonists — to me Dick Waterman was always the Good Guy in this movie, and I am very glad I took the chance to ask him about it. Here I set out the story of that long ago night as best I can.

Related: