John Fogerty and the songwriting canon he built with Creedence Clearwater Revival are forever etched in the crackle of vinyl and the thrum of new car speakers alike – the sentiments, struggles, and stories of a past generation that feel no less profound today. The bad moon that signals impending doom. The sunlit promise glimpsed through the back door. The “someday” that feels more like a crushing weight when you realize it’s always just out of reach. The candle in the window that lights the way home to rest your travelin’ bone. The lost connections and plans that fell through. The jangly chords that chase tomorrow (tonight) and demand to be played at a volume that brooks no compromise. Because anything less would be betrayal.

Fogerty was recently honored at the American Music Honors, joining a distinguished lineup that included Smokey Robinson, Emmylou Harris, Tom Morello, and Joe Ely. Hosted by Bruce Springsteen, the evening celebrated artists whose influence on American music runs deep. In his induction speech, Springsteen praised, “In one of his greatest songs, John Fogerty sings, ‘If you get lost, come on home to Green River.’ Now, his music feels like our national home.”

Encased in amber, the grain of their sound and the weight of their meaning have only deepened with age—now revived and redefined on Fogerty’s Celebration Tour. And there I was, lucky enough to see it all unfold in real time, as the punchy downstrokes on “Bad Moon” cut clean through the fading twilight of a Florida Strawberry Festival spring evening. Then, without missing a beat, a quick slide up the neck caught the rising wind and swept us “Up Around the Bend.” As you drive into Plant City, FL, the “neons turn to wood,” but take one step into the festival and those neon lights flicker back to life, casting their glow late into the night.

And a glowing, festive night it was. “I just got my songs back and I’m playing every one of them,” Fogerty proudly declared. As of January 2023, ending a 50-year legal battle, he owns the primary rights to his songs again. The copyrights were the property of Saul Zaentz, the owner of Fantasy Records, who sold the label and its publishing portfolio to Concord Records in 2004. Fogerty, who extricated himself from Fantasy in 1974, saw his artist royalties reinstated and increased by Concord. Even so, he was not able to gain ownership of his songs.

But now the songs have come back home.

“Green River,” its low-end rumble radiating with earthy depth, offered a moment for fans to feel Fogerty’s deep-rooted connection to the music of his youth—artists like Lead Belly, whose low tunings on his 12-string guitar shaped Fogerty’s approach early on. The next track, “Born on the Bayou,” swelled with his unmistakable tremolo effect, its swampy vibration rising as if drawn up from the soil of the bayou itself.

He then shifted our attention to his 1969 Rickenbacker 325 Sunburst and its “checkered past.” The momentum from the hit “Suzie Q” prompted his decision to “get everything set up to try and have a big career in music,” he laughed. He made ample changes to the guitar, most importantly the installment of a Gibson humbucker pickup.

Following CCR’s disbandment circa 1973, feeling emotionally detached and distant from it all, Fogerty gave his most treasured possession to a young boy backstage. Presumed lost for all those decades, it ended up in the most unexpected of places: wrapped in one of his signature red flannels under the Christmas tree – courtesy of his wife, who went on a secret quest to find the long-lost piece of music history. He looked to the screen at a picture of himself unwrapping the guitar. “I got my baby back! And you notice I haven’t changed my clothes in 44 years,” he joked, wearing a red flannel.

The gift moved him to tears. That Rickenbacker was with him when they played The Ed Sullivan Show, followed by Woodstock. When Fogerty got back to California after their Woodstock appearance, he wrote “this song on this guitar,” he said, pointing to the instrument, before slipping into the soothing strum of “Who’ll Stop the Rain.” In the most literal sense, it rained so much on Max Yasgur’s farm that it seemed to beg for the refrain. But in the broader sense, frustrated by social mores, it’s a song with dual allegorical meaning. It speaks not only to the discomfort of a festival crowd but also to the collective disillusionment of the day. As the war effort advanced, it became a question of who would stop the rain of conflict, confusion, and complicity on the ground. That question still hangs in the air – still, too often unasked. I’m still asking. But on a night like this, listening to its lush perfection, it offered something that at least felt like an answer. And then a salve all its own came the classic country daydream “Lookin’ Out My Back Door.”

“Rock and Roll Girls” came alive with Rob Stone’s sax solo – a part Fogerty originally played himself on the Centerfield album, along with all the other instruments. As Stone took the lead with bright, brassy lines, he dashed across the stage, his contagious energy matching the vitality of the song. Emerging amid expected setlist staples, “Effigy” struck my ears as an unexpected treat. To me, it holds the key to being the haunting undercurrent of “Fortunate Son.” If one shouts with fire, the other smolders with the silent majority not keeping quiet anymore. Each chord tensely builds to vocals that ask, “Who is burning?” before retreating into a composed but relentless “why?” A downcast tone underscores the sorrowful aftermath of the same system’s cruelty, and when he hits the low E with such striking force, it gives the song the treatment it calls for. Almost untouched by time, it felt as though Fogerty and his Travelin’ Band were channeling the studio version even as they subtly reinvented it live.

In a tender pivot, Fogerty played the love ballad “Joy of My Life” to commemorate his 34th anniversary with his wife, also dedicating it to us, his fans. “Fight Fire” and bonafide bop “It Came Out of the Sky” quickly reignited the energy, while the extended jam on the driving blues “Keep on Chooglin’” transcended it. Watching Fogerty tear through the set with sons Shane and Tyler at his side, the songs felt reborn in their hands. “I get to do this with my family, and that makes it absolutely the top of all emotions a person can have. We’re finally here. This is what we’ve been waiting for. There are no restrictions. I get to play my music in a truly joyful way.” Earlier, the brothers’ band, Hearty Har, opened the show – cutting a true Fogerty figure with their psychedelic, percussive, classic rock-informed sound.

“Centerfield” was next, bringing the fanfare of a seventh-inning stretch. Among the many honors Fogerty has received – including induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, the BMI Icon Award, and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame – a special recognition for this song made him the only musician ever honored by the Baseball Hall of Fame. Drummer Richie Millsap made his own mark on “Down on the Corner,” both sticks working different parts of the kit to create what sounded like layered cowbell accents. The longer he held the intro, the more the excitement built—the crowd clapping and cheering—until the groove finally landed and the place lit up.

A touchstone of songwriting and guitar economy, Fogerty has always pushed his creativity to the hilt, while also knowing “you can only put so much water in the glass until it spills out,” as he cautions in his memoir. This melody works, but find a better one. These words might do, but find better ones. If you’re John Fogerty, not only do you find better words and melodies — you melt them together like butter in a pan, used to perfection before they exceed their smoke point. This creative precision is exactly why it would be impossible to fit every one of his hits into a single setlist. In a film shown to preface the performance, he shared: “When I find a good lick on the guitar, it seems to open some sort of door and the rest comes out. The official song is the melody and the words. But for a kid listening to rock and roll, to me the music was just as important.” And as for that voice, it carries the song. And it carries me. With every baritone pang, a quiet emptiness inside me stirs, somehow leaving me feeling a little more whole. And with every higher reach, I continue to be carried by a voice that’s seen the rain and sings like the beauty of a sun shower. Which is exactly what happens when “Have You Ever Seen the Rain” plays into the set.

The age-old tale of a young musician signing a bad contract with an ersatz record company executive is one Fogerty knows all too well. The lyrics of “The Old Man Down the Road” echo that history: “He bring a strong man to his begging knee,” he sings in the first verse. A solo “comeback” hit, to put it reductively, it became the centerpiece of one of the most absurd copyright infringement cases: the very man Fogerty wrote the song about sued him for plagiarizing *checks notes* himself.

CCR bassist Stu Cook once remarked that “The Old Man Down the Road” sounded like “Run Through the Jungle” with different lyrics—a passing comment that helped spur Saul Zaentz (then still at the helm of Fantasy Records) toward legal action. The result: Fantasy, Inc. v. Fogerty. During the trial, Fogerty took the witness stand with his guitar in hand, playing excerpts from both songs to highlight the differences in melody, lyrics, and structure. The jury sided with him, determining that “The Old Man Down the Road” was not a copyright infringement of “Run Through the Jungle.” The case became a landmark precedent.

When Fogerty later sought to recover his legal fees, the matter went all the way to the Supreme Court, where he won again. The ruling eliminated the “dual standard” for awarding attorney’s fees, replacing it with an evenhanded approach. Though both songs bear his creative DNA (because he wrote them), he successfully defended them as distinct compositions.

In the second verse, he sings with the kind of abandon and righteous indignation I’ll never get tired of hearing: He got the voices speakin’ riddles/ He got the eye as black as coal/ He got a suitcase covered with rattlesnake hide/ And he stands right in the road.

The hook riff slithers between verses, mirroring the deceit and venom at the song’s core. And in the context of the Celebration Tour, where Fogerty now owns his music for the first time in decades, it stands as a hard-won revival. As the current live version uncoils into a longer finish, he trades solos with son Shane in a moment of musical chemistry, shared passion, and the freedom that now surrounds it.

CCR is one of those bands that changed the way I heard music as a kid—but Fogerty was my earliest memory of someone changing the way I saw music. I can imagine Tom Morello, who recently interviewed him at SXSW, shares a similar reverence for the impact his music has had. “Fortunate Son,” the defining protest anthem as we know it today, was a long time in the making—and yet took almost no time to write. A second-grade-aged John Fogerty was sent home to watch the Eisenhower inauguration on a black-and-white screen. Even at that age, he was suspicious of the big black limousines and the kind of people they carried. Watching political conventions, hearing the phrase “favorite son” tossed around without a second thought, piqued his curiosity. The words stuck. They lived in his head. Cut to 1966: Fogerty is drafted into the Army Reserve, while senators and rich tycoons manage to keep their sons out of the war. By the summer of 1969, the same year CCR briefly eclipsed the Beatles, he began writing around the phrase that had never left him. All those thoughts poured out in a raging torrent, and 20 minutes later, he walked out with “Fortunate Son.”

I carry my family’s story, of which I am a member of the first-generation chapter born on U.S. soil. After escaping Vietnam in 1973, my family arrived in South Florida by boat, among a wave of refugees welcomed by American sponsors. To hear Fogerty, over 55 years after that song was written, my presence at his concert felt like a peaceful kind of full circle. Its own way of saying thank you.

The same voice that wrote “Fortunate Son” is now the one celebrating the return of his own legacy. Speaking again of his rights recovery, Fogerty took a moment to give credit where it’s due: “You’d probably think it was some lawyer in a tall building that made this happen, but actually it was my dear and beautiful wife Julie that made this happen. She was relentless. She refused to take no for an answer. She got in their face, and by golly she got ’er done. I got my songs back!”

After pouring himself a glass of champagne, he quipped, “All night long I’ve been looking out there at these strawberries. If you saw me look a little pensive, it’s because I’m trying to figure out how I can buy a strawberry for fifty cents and then sell it for nineteen dollars.” He settled back into a more serious tone, looking out in all directions so as to address each fan equally. “Anyway, I wouldn’t be standing here if it wasn’t for you, and I know that deep in my heart. I am so full of gratitude for all the kind wishes you’ve given me through the years. Thank you for singing my songs. Thank you for carrying me in your heart.” He raised his glass with a sincere, “Here’s to you. I love you.”

And with that, he launched into the encore with “Travelin’ Band”—now the namesake of the group backing him. What was once a breakneck ode to the road is now both a mission statement and banner reclaimed with equal parts joy and delicious defiance. “Proud Mary” was the official curtain call. That pain-erasing, babbling brook of a solo danced across those warm D, G, and B strings, easing us into the final chorus that smiled through the parting.

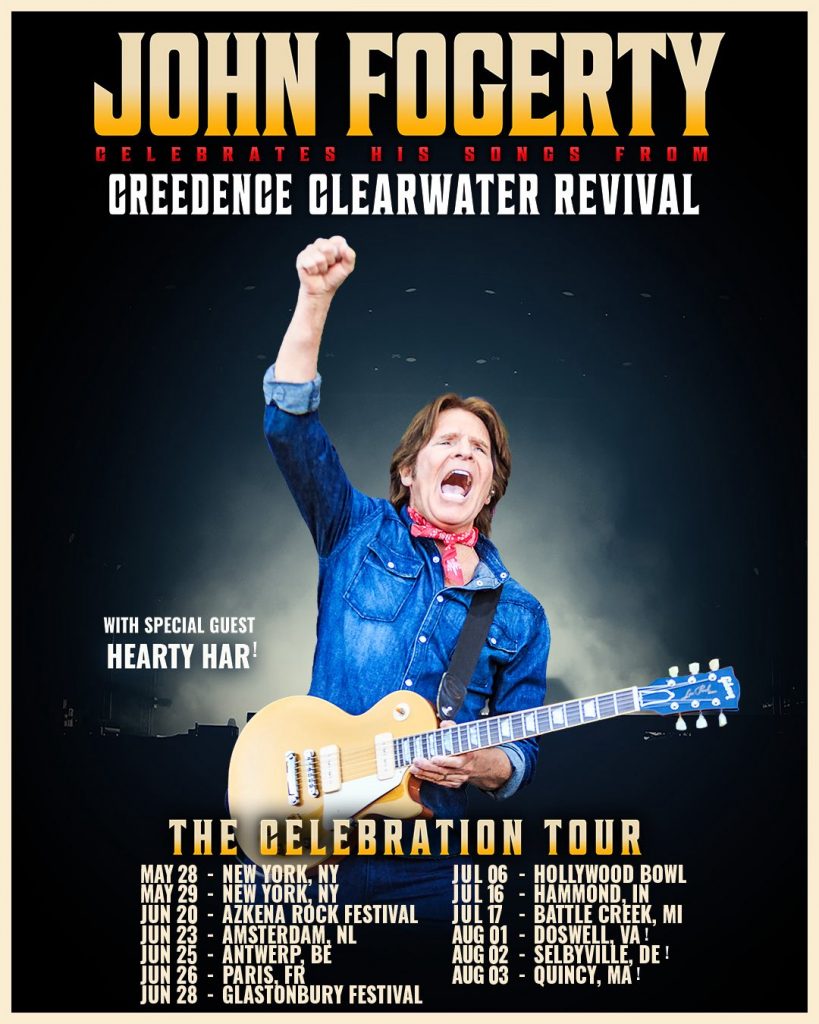

After wrapping up a standout performance at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, the Celebration Tour keeps on rolling, extending well into the summer with stops across the U.S. and Europe. The next major highlight is a special 80th birthday concert at New York’s Beacon Theatre on May 28. Due to high demand, a second show was added for May 29. For tour information and tickets, head here.