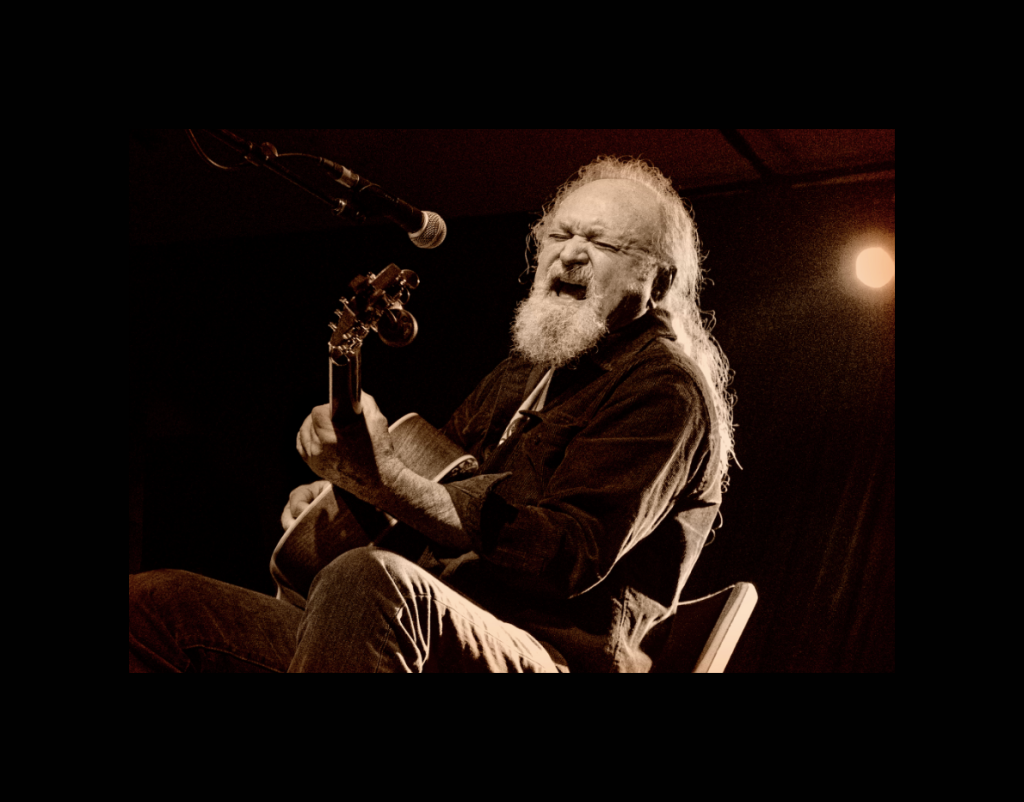

Tinsley Ellis is a friend. I’ve long ago stopped treating him from the distance of a journalist making objective observations. I’ve been writing about him for more than three decades. I can count on him to be a master at whatever he decides to do. Now half a century into his career he effortlessly has made a left hand turn from being a blues rocker to being an acoustic artist who’s as much at home with a 1937 acoustic guitar playing a coffee house like Caffe Lena.

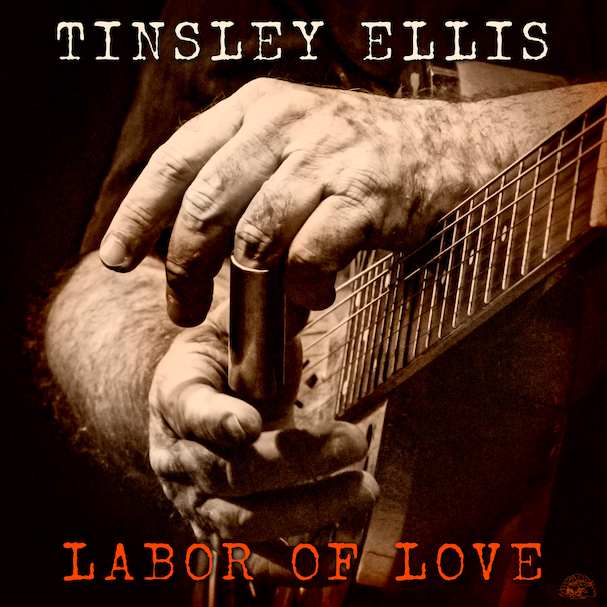

He’s gone from more than three decades rocking out with a band pushing the edges of a hybrid sound that could as easily teach Eric Clapton a thing or two to being a legacy sharing Son House chords with audiences around the world. Labor of Love is his aptly titled second acoustic album, following up on Naked Truth released in 2024. That album had nine originals out of 12 total. This time all 13 are originals.

“I don’t want to make the same rockin’ band album over and over again, and I kind of had to talk Alligator into letting me do that. We were all surprised about what a good response it got. It was number one. Bruce Iglauer (Alligator CEO) is a tough task master for sure, and he was skeptical similar to when I made and did a self-released all instrumental album in 2013.

“I took it to Alligator, and Bruce was skeptical, and so I started my own label, and they were skeptical as well. Something different is scary, but it was received as well especially in the blues radio world where Naked Truth was the number one album of the year above all those large names like Kingfish and Keb Mo. The second time I said I have a new album. I said, “Well, we do these acoustic shows,” and they said, “See, we do these acoustic shows, you know, just so happy doing it. I think they picked up on that. So, there was no argument this time.”

I asked Tinsley if he sees his two acoustic albums as being retro? “It absolutely is retro. Retro is a bad word because it means you’re trying to recreate something, but this is more traditional, and if I go and put on music to listen to I pretty much always put on Skip James or Peter Green or something from you know, back in that era. There was a time back in the mid-’60s to mid-’70s, the Fillmore era that’s kind of my sweet spot with Buddy Guy and Jr. Wells playing together on The Hoodoo Man Blues with rock and rollers. Peter Green was still with Fleetwood Mac. Duane Allman was still alive. I call it the Fillmore era if I listen to something. I’ll put on the Vanguard label or Delmark or early Alligator stuff, and so I guess truly am stuck in the past, but not in a Sha Na Na kind of way. Then, it becomes like oldies, and that evolved wardrobe and stuff like that. I don’t want to get involved in anything that involved wardrobe.”

Tinsley will never be accused of being schtick!

“I had some things that go back in the years and look at the pictures of me performing in a leisure suit or something. What was I thinking? I want to have more of the Butterfield Blues Band kind of way”

Is there any downside to being a white guy in a black form?

“Well, Muddy Waters said it best. Somebody asked Muddy Waters how he felt about all the Butterfield Blues Band, Cream,and stuff like that. Muddy Waters said, “Well, they’re great guitar players, and they can play circles around us, but I believe we can out vocalize them.” The vocals are always the weak link in a Caucasian blues act.”

Tinsley has been woodshedding with Jimmy “Duck” Holmes. Did Holmes give him any suggestions in how to handle that? “No, he’s a pretty laid-back guy and a man of very few words. He’s more into stuff like how to tune your guitar because all the guitarists in Bentonia use a special guitar tuning: Skip James and Duck Holmes and Jack Owens and Henry Stucky. They tune their guitar to a minor cord. E minor is how he tunes.

“We talked about that a lot, and we played, and he would stop me. “No, you gotta bear down with your thumb more.” Got me to put my thumb into it, and it’s more like that. Thumb more. He didn’t once talk about the song structure, the lyrics or anything like that – more talking about the guitar playing.”

How is Holmes’ influence reflected in this album?

“Well, I went over there to perform, but it was more like a guitar lesson from him. He greeted me there in the afternoon. It’s basically a juke joint. It’s like a grocery store. There’s no stage or lights or even a PA to sing through a guitar amplifier. Nothing separates the audience from the musician, but he gave me a little lesson in the afternoon when people were coming in, and I was hanging out and buying beers. Some other people were coming in and were playing along with us, so that was the real beauty of it.

“We did a show at night where I played, and he played, and I backed him up, and he decided to have the concert outside on the porch. So, people would sit out there drinking beer outside on a little town street, and his place appeared to be the only business that was open. I didn’t see any other stores or anything. There were storefronts, but Bentonia, Mississippi is not a booming metropolis.

“We were set up to play and dragging the guitar amps up and stuff, and the electricity went off at 6. So, just sitting around getting dark. There’s no electricity, and Jimmy ends up running an extension cord. We ended up running the whole concert out of his pickup truck and our extension cords, which is so Mississippi really, and the power never did come back on.

“All the while I was playing my set, there was a big boom. I looked down the block, and everybody was watching me play out there in the parking lot along the street. They looked to their left. I looked to my right, and there was a big mushroom cloud, and a big fire started. Jimmy Duck Holmes said, “Keep playing,” and I said, “What is it?” and he goes, “The fire department.” Their fire department burned to the ground while he and I played. It was a very eventful evening. I guess something sparked, and there was a storage of fuel there, and the whole fire department burned to the ground. People watched that, and listened to us. It was unreal.”

Somebody once told this journalist, “White blues men never slept under a hollow log.” Are there any disadvantages to being white in what Tinsley does?

“(Pause) well, uh, compared to Son House and pretty much all my idols I come from an infinitely more privileged background. There’s no denying that blues music is an African art form. So, that’s why I always pride myself on (being) a rock and roller who loves the blues because I don’t want to co-opt something I’m into.

“So, I just like the way blues music sounds as much like Elvis Presley loved the way blues music sounds, and he played it and felt that it improved his background. It improved his experience. I felt the music I like through my background and my experiences, and I try not to think about it much. I think if I were to declare myself a blues artist, that might be somewhat presumptuous, but if somebody wanted to call me that, I would take it as a very high compliment.”

If Tinsley were writing this piece, what adjectives would he put before his name?

“They always talk about the fact I’m from Georgia, and that always conjures up Ray Charles or the Allman Brothers Band, Little Richard. So, the Georgia thing and blues rock. But now I’m folk blues. Folk blues is a legitimate daughter, really. You think almost like Spider John Koerner and Dave Ray and like that.

“Back then (the 1960s) I saw bluegrass artists like Earl Scruggs and Doc Watson. I used to see them, and now there’s a whole crowd of them. If an African-American was playing bluegrass I think there would be a lot of acceptance, and hopefully me going out there and every once in a while, covering old blues is met with the same embrace. The blues community is very embracing compared to the pop music community ’cause pop music is driven by two things: youth and image—which means I’m screwed. But blues music…”

I told Tinsley that as a journalist being in this for almost six decades, I think his image is cool. That picture of him on the back cover of Labor of Love says a lot about his being part of the fraternity. I don’t see that as a disadvantage at all.

“Well, I’m kind of like a maniac on the back of that cover. If you went into a convenience store looking like that, they could probably call the law on you. I don’t have any costumes or anything. Consequently, I’m not going to be invited to perform in the halftime show or anything. I think it’s more of an everyman thing. I don’t wear a blue collar or white collar. Probably no collar. I’ll never go out of style, by the way.”

Tinsley is a talented 21st century bluesman, and I’m honored to be one of his friends. “When I did a tour with James Cotton and Joe D. Williams, the stories they would tell about older guys like Sonny Boy and Little Walter and Bo Diddley, unbelievable stories. I wish I’d taped it, but I do remember all of them. I’d sit and listen to Joe D. Williams talking about Bo Diddley, what a nut he was. He told me they’d get to a town and check into a hotel. Bo Diddley would go right to the maid’s station at the hotel and start chatting up the maids there at the hotel.

“They’d check into the hotel and Bo Diddley would put the suitcases in the room and go right to the maid’s station. He told Joe D, he goes, “I see you talking to these women at these nightclubs we’re playing. Guys, we got some perfectly fine women right here in the hotel.” And Bob Margolin who’s in the back seat trying not to chime in, “Muddy Waters married the maid in Gainesville, Florida.” Very good.

“That’s where he met his wife. You know, there are those kinds of stories, and that’s a pretty PG story right there. The X-rated stories are just outrageous and Nappy Brown, too. We backed him up in the ’80s. He’s talking about Little Richard and Buddy Guy being in the Apollo Theater in the 1950s at the Allen Freed shows and stuff. They were some wild people – Little Richard, particularly.”